INTRODUCTION :

Shaw is a sculptor with extraordinary diligence and dedication, which in turn leads to an often-missing prerequisite – monumentality. With Tim Shaw, that elusive element is always present, in small maquette or larger form. The work is iconic. It is therefore appropriate that Shaw was commissioned to make The Drummer. The result fully represents the determination of people and place - balanced defiantly on the edge. In his Artist statement he has spoken at length and in detail about the specifics of the project and its relationship to its site. However, it seems important for me to introduce by focussing on the permeating subjects within Shaw’s work as a whole, and how these themes have culminated in ‘The Drummer’s’ pervasive importance - not just to the centre of Cornwall, but to Tim Shaw’s oeuvre and to the wider context of artistic history...

Read more/less

Shaw’s work deals with primordial human instinct, laying it bare, never flinching from confronting us – with darkness and light. The need to recollect such truths is vital the more progression shields us from some of our fundamental characteristics. The yearning for such works of art becomes more and more important by way of resistance – to remind us who we really are. Shaw earlier stated, “There is a need for me to give shape and form to the emotive forces that lie beneath the appearance of everyday reality.”

Reaction to the work in the past has been extreme – ‘Silenus’, a larger than life figure, with antlers, holding his erect penis and staring unnervingly into the eyes of the viewer made National news when it was attacked by a masked man with an iron bar whilst on exhibition in the East End of London in 2007. In mythology, the wise old fool was tutor to Dionysus. As with much of Shaw’s work the mythological or historic thematic structure merely underpins a contemporary concern. A subtext for this defiant, conceited figure was the sneering frivolous nature of power, a warning of an inherent corruptive human element. This piece was originally envisaged as part of the installation ‘The Rites of Dionysus’ on permanent display at The Eden Project linking closely to the mythology of the bacchanal, but giving shape to perennial extreme facets of human nature acted out in full on life’s stage.

From mid 2007 to late 2009, a substantial body of work was realised during Shaw’s residency in London, where he lived and worked in Kenneth Armitage’s former studios as recipient of the Kenneth Armitage Fellowship. Drawing from personal experience of his formative years growing up in troubled Belfast, Shaw made a series of works focussed on world conflict, and the emotive forces that propel and perpetuate acts of extremism. ‘Tank on Fire’ was made; taking inspiration from images of events in Basra where an ignited soldier flees a burning tank. The piece was announced winner of the inaugural Threadneedle Judges Prize. Shaw also made ‘Man on Fire’ a double life-sized figure propelled uncontrollably forward whilst engulfed by flames. Shaw stated of these works, “I tried to imagine the thoughts and feelings of someone consumed by fire, of someone who is caught between two worlds, that of life and death”. The culmination of the residency was ‘Casting a Dark Democracy’ a 17 foot sculpture of the Abu Ghraib prisoner stood in front of a mirroring pool of oil on a sand covered floor. A smoke filled low-lit room, and drumming heartbeat pulse completed the installation. The true cost of conflict, fear and greed made palpable. Jackie Wullshlager, critic for the Financial Times heralded the piece ‘The most politically charged yet poetically resonant new work on show in London’ whilst Gilda Williams of Artforum stated ‘Shockingly powerful… I’d assumed that no work could ever match the impact of the actual newspaper photos, but Casting succeeds”.

My last experience of working with Shaw was on the 2008 exhibition ‘Future History’, which took place mid-way through the residency. The exhibition was a mixture of maquettes of images of conflict alongside a series of ‘Fertility Figures’ and ‘Funerary Figures’. In his catalogue introduction Shaw confronted an initial concern over, what could be termed, disparate subject matter, stating, “At first glance the work pursues two distinctly different paths, one deals with current affairs the other has its roots in something much older... Perhaps one thing that binds it together is to do with the most primal of all concerns which is the will to exist.”

After the productive residency in London, Tim returned to Cornwall to begin this intensive period of work on The Drummer.

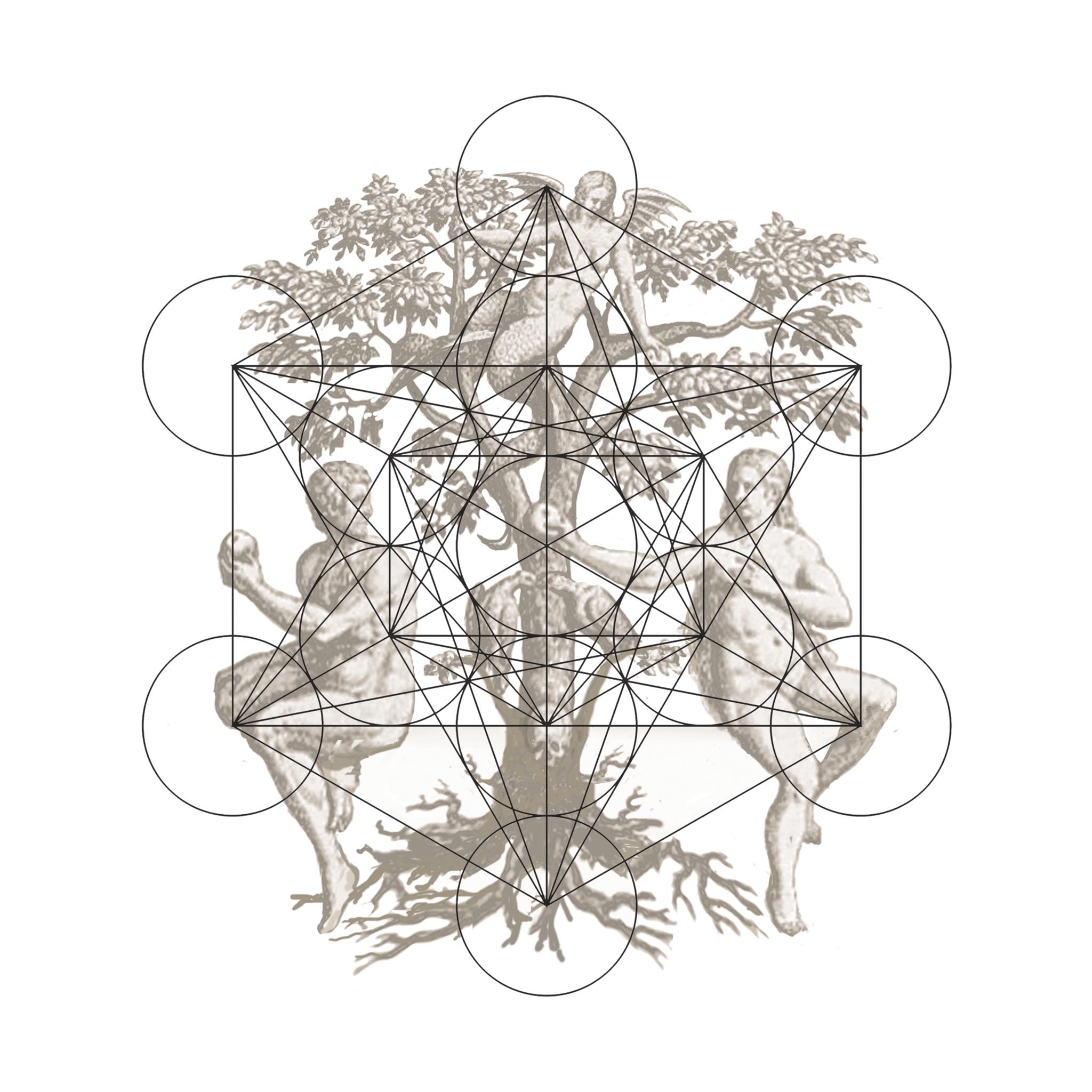

Featured as part of this exhibition is the early installation; La Corrida - Dreams in Red, made from 1996 to 1999 after a three month residency in Andalucía. It is a depiction of a stage that rages with energy, passion and grace. Elements of beauty, sensuality and brutality merge. All participants vigorously alive, yet at all times intensely aware of their mortality. Amongst the ensemble sits a flamenco dancer elegantly balanced on large spheres. It was the first use of this universal symbol within Shaw’s work. Shaw once told me of a profound moment which occurred after the death of his Father - when he asked his Mother if his Father had passed peacefully she said ‘he slowly drew back less and less breath until finally if was as if a great ball of silence had filled the room’. This powerful, poetic notion becomes difficult to elude and adds another layer to the significance of the ‘orb’ symbol.

The origins of The Drummer could be seen as the seeds that drive all of Tim Shaw’s work, the pounding pulse of existence, the defiant yet graceful balance on a precarious ball of uncertainty representing forces greater than ourselves. The Drummer will stand as a centre piece to Cornwall but will also stand as a permanent monument to the ephemeral state of balance between life’s resolute, magnificent endeavour and the unknown which awaits us all.

Joseph Clarke. 2011

ONLINE CATALOGUE (click below) :

ARTIST INTERVIEW FILM :

EXHIBITION VIDEO TOURS :

THE DRUMMER

A Symbolic Work that Celebrates the Spirit of a Land and its People

It was no surprise that when I first set foot in Cornwall, twenty five years ago, I described it as a place whose drum beats differently to anywhere else, referring to the primordial, magical and timeless aspect that the land possesses. This came to mind, when in 2007, I was invited for the second time to submit a proposal for a sculpture for Truro’s Lemon Quay. I viewed the opportunity as a chance to celebrate something that would reflect an aspect of Cornwall and its people, and not just the city...

Read more/less

What does it mean when we refer to Cornwall as timeless or magical and what makes this County different from any other? The search for answers led to walks across moor, coast, and underground into the tin mines, to conversations with different people, from all walks of life. “You could feel the black,” an ex-miner described the thick, stifling, dimly lit atmosphere of his subterranean working environment. It’s a description that had profound resonance.

After some thought, I concluded that Cornwall in modern times is better known as a tourist destination and a place where many people have chosen to settle. There is, however, something more fundamental that defines the peninsula. Many miles from the country’s administrative centre, poised on the edge, jutting out into the great Atlantic Ocean; Cornwall is geographically and to some extent, economically remote. The shared sense of magic and timelessness that one feels not only comes from the barren landscape and rugged coastline and from the quality of light the peninsula possesses, but also from the dereliction and desolation left over from a by-gone industrial age. Living in a remote place often brings some kind of hardship. Perhaps it is this that has instilled within the nature of its people, a quiet and proud sense of independence paralleled with an instinct to survive whatever the prevailing circumstances may be.

In the archives of Truro Museum there is an extensive collection of photographs of tin miners working underground around the turn of the 1900s, taken by the photographer J.C.Burrows. One photograph in particular, portrays seven men standing in front of a mineshaft. The image is both haunting and austere; the subjects look sternly into the camera lens, they are united by life’s hardships, which are etched into the faces of each and every man, a look that is more difficult to find in Cornwall today.

It is perhaps then, the men and boys that mined tin for generations in the heat and darkness below ground level, and the fishermen that battle against the sea that best describe the spirit of ‘steely resilience.’ It is exactly this that The Drummer celebrates as it forces a mighty blow upon the drum.

The ball on which the figure balances relates to the sea, earth and the bright moon that shines across expansive night skies. The composition originates from an installation entitled La Corrida ~ Dreams in Red. The decision to use the ball was inspired by the quay’s circular paving design, which refers tothe tidal water beneath it. The ball suggests both a sea buoy and the globe across which a great many Cornish people migrated to find work.

The Drummer sculpture is cast in bronze, an alloy composed of copper and tin. The cast contains both an ingot of Cornish tin and Cornish copper which has been symbolically thrown into the crucible during the smelting process. The emblem of the lamb and flag embossed upon the drum represents purity and refers to Truro’s past as a stannary town where tin was weighed, stamped and sold. Situated midway between Land’s End and Saltash, Truro has traditionally served its rural community as a commercial centre. In turn, the Drummer brings to the heart of it a sense of the rural community through which it celebrates the rhythm and beat that drives many festivities throughout the county: the Helston Floral, Penzance’s Mazey day, St Just’s Lafrowda and that most primal and magical of rites, The Padstow Obby Oss and more recently, Truro’s winter city lights.

Twenty-five years on from my first arrival in Cornwall, it is an honour to have been commissioned to create this work. It is uncanny, yet fitting, that the sculpture, which endeavours to define something about Cornwall and its people, should have been created in a disused quarry building in a remote location that was once the centre of the granite industry where rock was blasted and shaped by masons. It is that same rock which paves the many streets of our capital, three hundred miles away.

Tim Shaw. 2011